Every Fire Starts With A Spark: The Spark Of Sussman Lawrence

How rock bands get started (1978)

After playing for a year and a half in Minneapolis’s own reggae and calypso band, Shangoya, I started another band called Sussman Lawrence with my high school friends —two of whom, included Andy Kamman my old band mate from sixth grade and my cousin, Jeff Victor on keyboards.

There’s no need to remind me, I’m quite aware that Sussman Lawrence was, and still is the single worst rock band name in the world, especially since no one in the band was named Sussman or Lawrence. The name started as my idea of a joke, and on principle, I refused to change it. I was convinced that having a band name which sounded like someone’s dad’s accounting firm subverted the New Wave rock tropes of the day. As the band’s unofficial fascistic leader I didn’t even budge when a slew of great alternative names came rolling in:

Jaguar Beach

Let's Run

The Groove

The Spanking Violettras

And this classic that we actually paid the late Bruce Allen of the highly–inventive Minneapolis band, The Suburbs, to come up with:

The Golfing Clowns

I couldn’t have moved further from my love of R&B and reggae than when I first started playing with the guys in Sussman Lawrence. They were great musicians, and because they had such great chops and could actually play difficult styles note for note, some of the guys were influenced by bands like Kansas, Boston, and Styx—bands so "white" they could burn out your corneas. On the other hand, the five of us getting together was nothing less than a miracle.

I’d played off and on with Andy Kamman since we were eleven and twelve years old. And because he was fearless enough and dedicated enough to the craft of drumming, he wasn’t afraid to try things that he couldn’t immediately master. That meant that as he was constantly learning and progressing upwards into ever more complex rhythmic styles, he would need to cope with the pain of sounding bad, even as he become better. Most people can’t do that. They learn something, they gain a little proficiency, they reap the rewards (whatever they may be) of that first level of proficiency, and they stay at that same level. People who want to progress aren’t afraid to feel the ignominious sensations they had as a beginner. Andy was that person. He was fearless and kept on getting stronger. By the time he was in 11th grade, he was one of the best drummers in Minneapolis. The fact that he lived down the block from me made it all the better. It was the same thing with Jeff Victor.

Jeff first heard me playing some old upright piano during a Saturday School class at my synagogue; we were around thirteen or fourteen years old at this point. I was working on some simple blues progressions, and he caught the music bug then and there, or so he told me. Up until that time, he had accomplished what most people who take boring piano lessons do: Absolutely nothing. But only a year later, he was playing Greg Allman songs and Bonnie Raitt. Not long after that, he was playing jazz standards and was able to improvise in any key, as well as the prog rock stuff I just mentioned. Like Andy, he kept developing on his instrument and his vocals too. It wasn’t lost on me how fortunate I was that Jeff is my cousin. We also became best friends around that time and began a shared passion that continues to this day.

Sussman Lawrence’s bass player Al Wolovitch, wanted desperately to play with Jeff and me. I think it was in the spring of eleventh grade, just before summer vacation when Jeff and I were practicing in one of the little soundproof booths in the band room. Al would come around, looking to jam with us. I didn’t mean to be a dick; I just didn’t feel like Al was cutting it. He couldn’t jam, didn’t seem to know what key we were playing in, and overall, he had no sense of groove. To this day I have never witnessed someone take on a new skill as quickly and as profoundly as Al did that summer. It wasn’t that he’d “improved” so much as he became, in less than three months, an astonishingly good, fully professional sounding bass player. Al was playing Jaco Pastorious solos note for note. He was tearing into Stanley Clarke songs, and breaking out the funkiest Brothers Johnson grooves imaginable. I couldn’t believe what had happened to him. He told me he’d just sat around for a whole summer, woodshedding on recordings by those players. Al also said something that sticks with me even now, “I just learned how to listen.” Yeah, it was deep listening for sure. That and his getting laid for the first time, was likely what turned him from, a skinny suburban Jewish kid, into a skinny suburban Jewish mother*cker on the bass. The other member of Sussman Lawrence was Eric Moen.

Eric played sax like Clarence Clemmons, and he played classical guitar like a young Segovia. To top it off, he looked like an even more handsome version of David Bowie. But like Al, Eric also wanted to play in a band with Jeff and me. Like Al, Eric was at first, another recipient of my egotistical, incurious assholic behavior. I hadn’t even heard Eric play a single note when I told Jeff, "that guy can be in the band if he can supply us with a PA system.”

When I finally did get a chance to hear Eric, I immediately dumped the PA idea. He was already a fully formed, highly creative musician and stage performer. I mentioned earlier that Sussman Lawrence was something of a miracle and I meant it. How else could you explain finding some of Minneapolis’s best musicians in your own high school? And except for Andy, who was a grade below the other four of us; how can explain the fact that we all happened to be in your same grade? To make the idea of our getting together feel even more miraculous, we were all best friends throughout our years as band mates, and we remain best friends —even today.

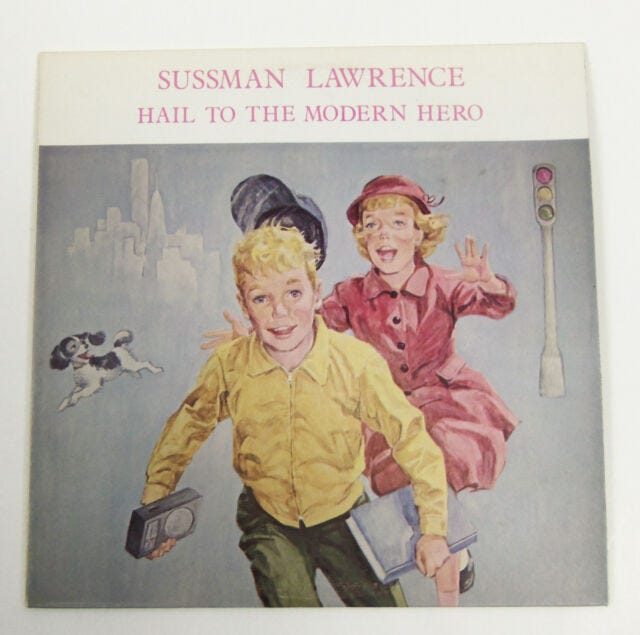

We were seventeen and eighteen years old when Sussman Lawrence recorded its first full-length album, Hail To The Modern Hero. The cover art was a perfect copy of an early Dick and Jane Reader, except that in the picture Dick was holding a transistor radio up to his ear and Jane was carrying a vinyl LP.

This was 1978 and in those days making an actual record was a rarity. It’s not like it today, where every musician from Dallas to Dar es Salaam can have, not one, but countless recordings of their music. Back then making a record required a musician to go into a studio with at least $250,000 of recording gear. That meant you needed a rich uncle to finance the thing. We did something a little different.